HRI Partnership Builds New Recycled Reef to Protect Goose Island State Park

Engineering Future Habitat

Recycled construction materials and oyster shell are creating the foundation for new life in Aransas Bay. The Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies (HRI) at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi is collaborating with Palacios Marine Agricultural Research, Inc., Derrick Construction Company, the Environmental Protection Agency and the Center for Coastal Studies at TAMU-CC to create nearly three acres of restored oyster reef in the waters off Goose Island State Park. The concrete barriers form the foundation for the reef and were covered with recycled oyster shells to provide the necessary surface to attract new oyster growth over time.

CORPUS CHRISTI, Texas – Recycled construction materials and oyster shell are creating the foundation for new life in Aransas Bay thanks to a reef restoration project. The Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies (HRI) at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi is collaborating with various partners to create nearly 3 acres of restored oyster reef in the waters off Goose Island State Park.

Oysters are an important part of the coastal environment, improving water quality, providing habitat for fish and other species, and protecting shorelines from erosion. But they’re in decline worldwide – it is estimated that 90 percent of native oyster reef habitats have been lost, compared to historic abundance. Contributing to that problem are unsustainable harvest and destructive dredging of oyster reefs. The removed shell generally ends up in the landfill after the oysters are consumed, leaving young oysters without hard substrates for attachment and building new reef.

“A lot of people love to eat oysters, but they often don’t realize what an important role they play in our environment,” said Gail Sutton, HRI associate director and co-founder of the institute’s Oyster Recycling Program, Sink Your Shucks. “They’re the water treatment plants of the bays — one oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water a day. They’re also a happening place to be underwater, providing habitat and nurseries for species like fish and crabs. When a reef dies or is removed, the water quality goes down and the fish leave. It’s an indicator of environmental degradation.”

Because of their proven environmental benefits, oyster reef restoration has become an increasingly popular environmental mitigation method in coastal communities worldwide. HRI has been at the forefront of oyster recycling and reef restoration for the last decade. Through its revolutionary Oyster Recycling Program, the institute has spent the last 12 years collecting more than 2 million pounds of oyster shell from local restaurants and wholesalers and placing it back into the environment to create new reef habitat.

Over its past decade of reef building, HRI has studied how best to build reefs that protect and enhance local bay habitats. Through its Coastal Conservation and Restoration Lab led by Dr. Jennifer Pollack, who co-founded the Oyster Recycling Program, the program has built 25 total acres of oyster reef protecting vulnerable shorelines and seagrasses in Aransas, Copano, and St. Charles bays. And they have seen the success of these projects locally – a 2,000 linear foot reef installed by HRI and partners immediately before Hurricane Harvey in Goose Island State Park incredibly survived the storm and saw new growth in the months afterward, Pollack added.

“We will be adding on to work we’ve undertaken for many years to protect the state park,” Sutton said. “We place these in special spots — we call them ‘boutique reefs’ — because the environment is so delicate. We’ve found our methods really work.”

It’s necessary to provide a strong base for these reefs such as concrete, river rock, or limestone to allow the shell to better serve its purpose of attracting young oyster larvae to attach and grow. Without it, the reefs will often sink into the soft muddy bottoms of Texas bays.

The cost of construction materials has gone up recently, however, and concrete to build new reefs was hard to come by. But when the Ed Rachal Foundation, a frequent HRI partner, found out about the predicament, it stepped in to donate nearly 3 million pounds total of concrete, along with the labor to mobilize the materials. Other partners include Palacios Marine Agricultural Research, Inc., a research partnership with HRI, Derrick Construction Company, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Center for Coastal Studies at TAMU-CC.

Over a period of several weeks, workers loaded the concrete barriers onto barges by crane. It took about four days to move all 210 barriers — at 40 feet by 2 feet, they each weigh about 14,000 pounds each. The barriers were placed end-to-end in a designated reef site staked out ahead of time. In waters six feet deep, they will be used to create four large mounds with space to allow water to pass between them. About 330,000 pounds of recycled shell will be placed on top, and the cycle of reef building will begin again.

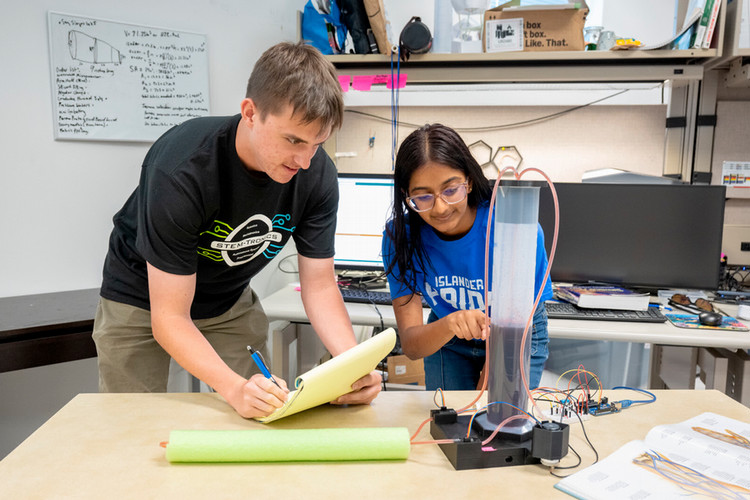

The reef will be monitored by HRI scientists and students after placement to study its performance over time, looking at the water quality, growth, and diversity of life of the reef. After all, you don’t just want to build a reef and leave, you want to see it thrive, Pollack said. Long-term monitoring helps officials to ensure these investments in the environment are a success over time.

“Our program is small but we’re vertically integrated, and we’re closing the loop,” Pollack said. “The people eat the oysters, we take the shell, we allow it to sun-bleach, we put it back in the water at the right times and in the right places, and we start all over again. And we’re making sure with our research that these reefs are a success for the next generation.”