GameStop was just a symptom, not the problem

(Note: This article was originally published Feb. 12 on the Texas A&M University RELLIS website, as a Faculty Focus article. The author, Dr. Dimitrios Koutmos, based at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi, teaches and conducts research on the RELLIS Campus. He is an assistant professor of finance with research specializations in asset pricing, banking, blockchain technologies, data analytics, derivatives and risk management.)

The last few months have seen unprecedented volatility in financial markets as well as uncertainty about the future for investors, both large and small, households, economists and other government authorities. Along with this uncertainty, many questions abound, such as where are we headed in terms of our economy? To try and answer some of these many questions, let’s explore what the climate is like, both on Main Street, Wall Street and in Washington DC, in order to try and figure out what the future has in store for us. As we do so, we will discuss a range of topics, including the recent GameStop conundrum, and what opportunities may exist in the future.

So, where are we at currently?

At the time of writing this, we are sitting on a stock market higher than we have ever witnessed in U.S. history, with the Dow Jones over 30,000 points and the S&P500 over 3,700 point.

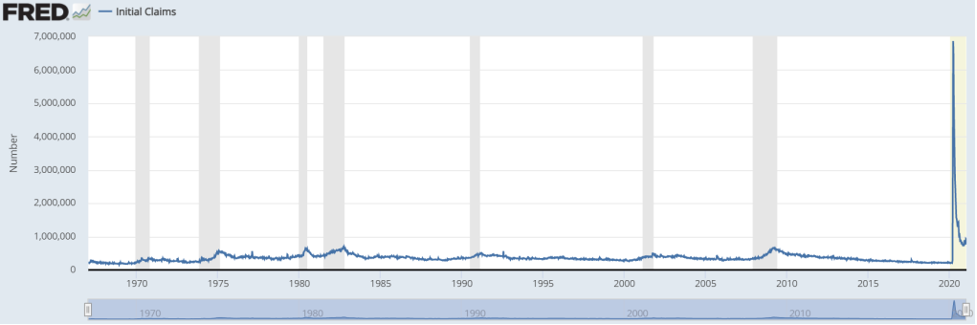

Meantime, initial unemployment claims recently spiked to levels that inconceivably dwarfed what we witnessed during the so-called ‘Great Recession’ of 2007-09 (see Figure 1). These initial claims represent the number of new jobless claims filed by those seeking to obtain unemployment benefits.

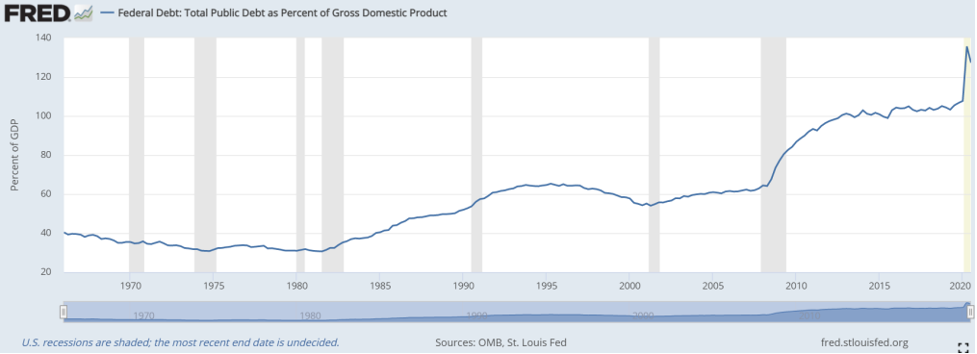

Additionally, federal debt (as a percentage of our GDP) has also reached levels that we have yet to witness in recent years (Figure 2). Economists are meanwhile split as to what we can do about this, or, more fundamentally, how much debt is too much?

Janet Yellen, who was recently appointed by the Biden administration to the position of Treasury Secretary, has signaled that enlarging the federal debt is necessary for further stimulus to fight the ill-effects of the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic. Last week, she urged Americans and fellow Lawmakers to “act big,” saying however “…neither the [President] nor I propose this…relief package without an appreciation for the country’s debt burden…”

It is important to note, however, that the level of debt the American economy is shouldering is mirroring what we witnessed in Greece during the 2007-09 period. In a 2018 published paper on the European Debt Crisis, titled “Interdependencies between CDS spreads in the European Union: Is Greece the black sheep or black swan?,” countries with high levels of debt can be exposed to what economists refer to as “contagion effects.” In other words, debt leaves one’s domestic economy more susceptible to outside forces, such as market crashes or bank runs from other countries.

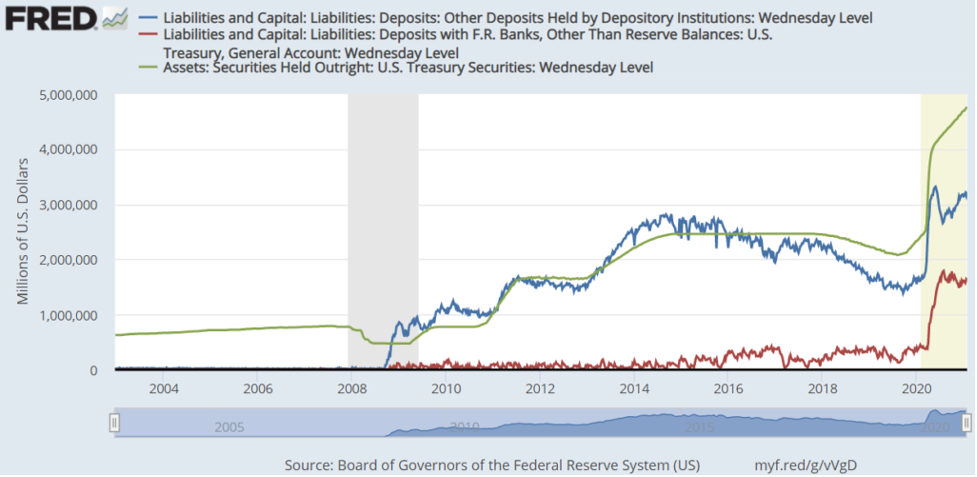

Where we will go from here also depends much on how the Biden Administration proceeds in terms of its economic and fiscal policies. Already, there appears to be little wiggle room for more expansive monetary policies, given that the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet has ballooned over time (see Figure 3). While we can see expansions in the Federal Reserve balance sheet during the 2007-09 recession, this level appears pint-sized relative to what we are presently observing. The Federal Reserve has also been purchasing a substantial amount of mortgage-backed securities, which could increase the probability of (or delay the occurrence of) another impending mortgage crisis. This leaves us with serious questions about how much more flexibility we have in terms of utilizing the Federal Reserve to keep markets quelled. These are questions that the Biden Administration needs to grapple with as it implements its economic and social policies.

How did we get here?

Depending on who you ask this question to, you likely will get very different responses. Although most can agree that the outbreak of Covid-19, and the resulting lockdowns that were mandated by governments around the world, caused negative shocks to our global economy. From February 2020 to March 2020, the S&P500 and Dow Jones each lost about one-third of their value. The market volatility we are experiencing is also the highest we have seen in recent years.

One point of view, and one that I encourage others to think about, is that interest rates in the United States have been too low for too long and this has resulted in a systemic buildup of risks in our financial system. Our (near) zero interest rate environment has enabled much of the “0 down 0 interest until…” purchase deals on major goods, such as vehicles and appliances. While these incentives may be alluring for consumers, they inevitably lead to rising prices, as individuals are more willing to purchase something that they otherwise would not be willing or able to.

This spending behavior, and disinclination to saving, is arguably one of the primary reasons why we are in the state we are today. Namely, stock prices are very high relative to fundamentals, such as company earnings, and our economy is highly sensitive to negative exogenous factors (factors outside of our control), as was shown with the initial unemployment claims in Figure 1. This view is not particularly controversial.

Federal Reserve Bank of Boston President and CEO Eric S. Rosengren stated in the fall of 2020, “…clearly a deadly pandemic was bound to badly impact the economy…however, I am sorry to say that the slow build-up of risk in the low-interest-rate environment that preceded the current recession likely will make the economic recovery from the pandemic more difficult…”

In response to GameStop’s unusual ticker activity, Richard Fisher, the former president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, told CNN Business, “…I think we’ve had a bubble for some time…this is just icing on the cake…when things get out of control like this, it is a sign that you should be very worried…someone is going to get hurt…”

As market volatility rises, and prices deviate further from their fundamental value, we can expect to see more odd behavior, such as what we witnessed with GameStop. GameStop’s unruly stock price behavior may be nothing more than a symptom to a much larger problem, as it is quite possible that stocks on aggregate are experiencing bubbles in their prices.

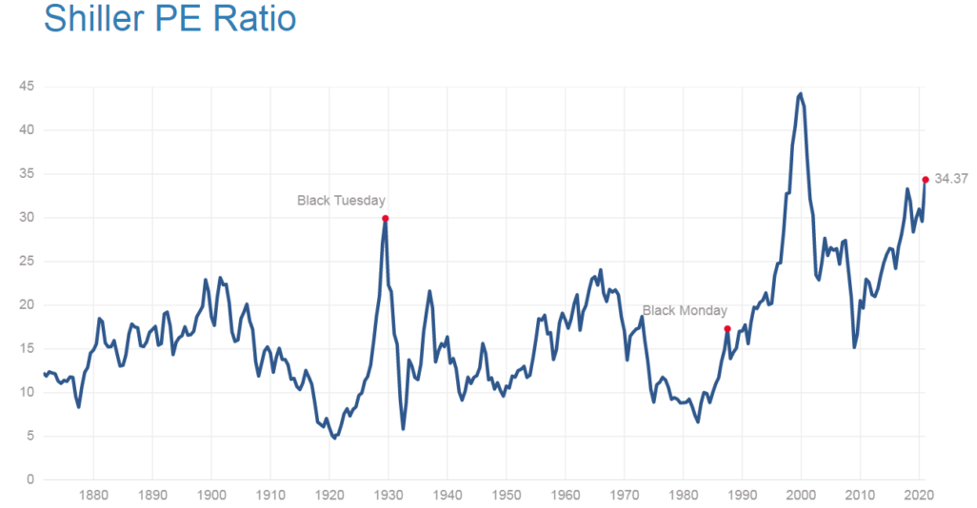

A graphical representation of how stock market prices compare to fundamentals can be gleaned from the so-called “CAPE Shiller PE ratio,” by Yale Economist and Nobel Laureate Robert Shiller (see Figure 4). This ratio, in general and non-technical terms, compares market prices to inflation-adjusted earnings. Again, prices is the numerator (something that is susceptible to irrationality, exuberance, or manipulation) and earnings is the denominator (a fundamental measure of value). If the Shiller P/E ratio gets “too high” relative to its historical trend, it can signal trouble. We see from Figure 4 that, presently, we are higher than where we were in 1929, 1987 and 2007-09.

In response to the buildups of risk in our economy, the federal government is signaling its willingness to bailout major corporations, such as airlines companies, and this can continue to set a shaky precedent in the years to come. We witnessed the controversial bank bailouts of 2007-09, and now the stage seems to be setting for more bailouts.

Where are things going in the future? How can a younger workforce adapt?

While much depends on what directions the Biden Administration takes, it is becoming clearer that technology is becoming a more embedded component of our lives – from the goods and electronics we purchase to the financial institutions we bank with. There are many deep and legitimate concerns about the role of BigTech in our lives, and these will continue to receive international attention. But one thing is becoming clearer: younger employees need to be well-versed with technology and should take time to learn, even on their own if they have finished school already. For example, if you are a finance professional looking to move up, it is very likely that more doors will open for you if you are well-versed in one or more data science program. It is no surprise that in the last year, there has been a surge of startup firms that teach machine learning to people of all ages and walks of life.

Another trend I believe will take place is the realization (especially on the part of the public sector) that entrepreneurship and small business ownership is critical to a healthy and resilient US economy. With the Covid-19 pandemic, we saw a plethora of small businesses close while, say, Amazon’s market value rose. This is not to say that Amazon’s employees do not work hard or its management “doesn’t deserve it.” On the contrary, we came to rely on Amazon for things such as touch-less delivery during this hectic time. What I am referring to specifically here though are the economic dynamics at play and these dynamics point to something unsettling: the concentration of economic power shifted, relatively speaking, from the hands of many to the hands of a few. With concentration also comes fragility. If resources, economic and otherwise, are concentrated in the hands of a few, this can mean trouble and more reliance on the government for initiatives to restore equity, or worse, to bailout those few. These dynamics also lead to a less democratic society.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), Department of the Treasury, as well as the Fed, are all fully aware of these types of dynamics, and in finance literature we refer to this as the “concentration-fragility hypothesis.” I thus expect the Biden Administration to make it a priority in restoring and empowering individuals’ abilities to engage in entrepreneurship and small business ownership. If done right, we should see a growth of small business ownership once more in the upcoming years.